Your Menstrual Cycle - Training and Nutrition

Gold medals and world records have been won and set at every stage of a woman’s cycle. By working with your cycle and making informed changes you can ensure you are at your best for every stage of your cycle.

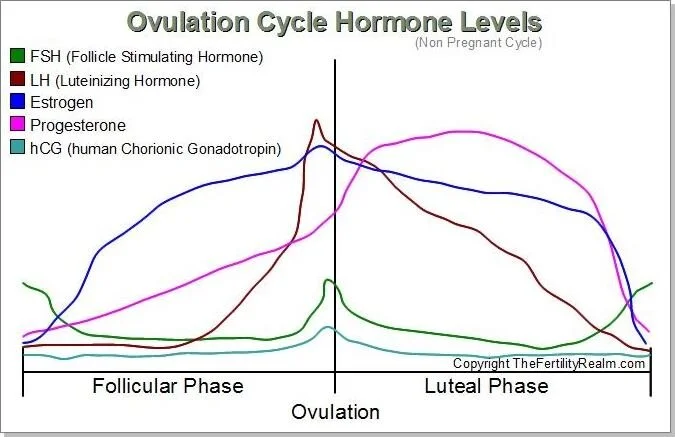

The menstrual cycle occurs in three phases: follicular, ovulatory and luteal. The first half of the cycle is known as the follicular phase and the second half of the cycle is considered the luteal phase. Midway through the cycle between days 12 and 16 ovulation occurs, known as the ovulatory phase. Each phase varies in the hormone balance, which can determine what type of fuel we use for exercise (carbs Vs fats). This also affects how we adapt to training. In the first phase women are similar to men in physiology, there is a two week period where we are a little compromised in the luteal or high hormone phase. But tailoring your nutrition and training can ensure you get the most from your efforts (3).

Follicular Phase

Training

First few days gentle exercise

Strength (1-5 reps) and hypertrophy (8-12)

Start to increase weights and intensities

Add some HIIT

Nutrition

PMS symptoms

Increased insulin sensitivity

Increase unprocessed carbs

Ovulatory Phase

Ovulation occurs around day 12-16

Training

Oestrogen peaks before ovulation. Studies that knee laxity increased between 1 and 5 mm between the first day of menstruation and the day following ovulation, depending on estrogen levels (1). Paired with increased Q angle in females, this leaves female athletes at a higher risk of ACL injuries. This is particularly important for coaches or athletes involved in sports which demand quick directional changes such as GAA, soccer or rugby (5).

Increased strength, endurance and pain tolerance

Now is the time for PRs

Nutrition

Around ovulation 100-200 extra Calories

BMR starts to rise

Moderate carbs

Recovery

Female athletes need more protein after exercise to recover and maintain lean muscle mass (3).

Nonfat greek yogurt is quickly absorbed and contains fast acting whey protein. Honey or maple syrup can be added to increase carb content (3).

Luteal Phase

Oestrogen and progesterone are at the highest. The combination of oestrogen and progesterone decreases the plasma volume or the watery part of our blood by about 8% (3). Our blood is a little bit thicker, so our effective circulation or the amount of blood that can go to our working muscles is decreased, so our power output is decreased, heart rate is increased. This also affects how much we need to hydrate.

The other aspect of high oestrogen and progesterone levels is our core temperature is up by 0.3 - 0.5 degrees Celsius. Therefore, our time to fatigue or the time it takes for us to get to a temperature at which the muscles stop working is shorter, so our intensity is decreased. Our ability to tolerate heat is decreased. Our ability to go harder longer is decreased just because of this rise in core temperature (3).

It breaks down our muscle tissue a little bit faster, which means we have a more difficult time recovering. It is very important to get protein in before and 30 mins after you train. It also increases our total body sodium losses, so we have less sodium available to go into our sweat (3).

Training

Begin to decrease loads

Circuit style training

Learn new exercises using low weights

Longer intervals

PMS – yoga, walking, low intensity

Nutrition

Studies show insulin sensitivity is decreased by 14.8% in the late luteal phase (2). From a training stand point it makes more sense to fuel with fats at this point as power output and intensity is decreased. Working muscles can be fuelled by fats rather than high power carbs.

Moderate carbs, increase fats

Due to the reduction in blood plasma adding water foods, salts and magnesium can be helpful.

Prehydrate prior to training sessions

Protein before and after training to negate progesterone catabolic effect on lean muscle mass. Recommendation is 10g before and 20-25g 30 mins after training. Replace sugars 90 mins after training (3)

Specific Nutrition Notes - Luteal Phase

Extra 200-300 Cals, often craving carbs but insulin sensitivity is still low so avoid bingeing. Stay satiated with healthy fats and lean proteins.

Serotonin is naturally low. This can be linked to low Oestrogen in the late luteal phase. Eating foods high in tryptophan, (serotonin precursor) salmon, turkey, eggs, pumpkin seeds, oats

Magnesium can help with symptoms of PMS. Cacao is a source of magnesium and can satisfy sweet cravings during the late luteal phase.

Studies have shown calcium and Vit D supplementation can improve regularity of the menstrual cycle in women with PCOS (4).

Sports Specific Nutrition

Eat before, during and after training

Generally, it is not a good idea for women to train fasted. It increases the amount of cortisol, which encourages the body to store fat and can increase overall stress. Overall stress then inhibits the body's ability to recover.

Typically training first thing in the morning you will have been fasting for 7-9 hours or longer overnight. In the morning your blood sugar is low and this inhibits your ability to hit higher intensities and you can’t maximise the training adaptations. Your cortisol levels are naturally high to help you wake up (3).

A 150 - 200 calorie snack is a great way to bring blood sugar levels up and to allow you to hit those higher intensities. Toast and almond butter or tahini or yogurt and sweetened nut milk, a recovery drink with a good amount of carbs could also be consumed for a liquid brekkie.

When planning nutrition for rides or runs, consider the work you will be doing during the session. For intervals, having a quick sugar source such as dried fruit or glucose tablets are ideal. Long steady rides slow release carbs like a clif bar, sandwiches or salted salad potatoes work well. Aim to consume roughly 3.5 cals per kg of bodyweight per hour (3).

60kg athlete needs roughly 210 cals per hour

Within 30 minutes of finishing training aim to consume 20-25g of protein (3). This will help you to recover quicker, allowing you to train hard again at the next session.Within 60 minutes aim to get some carbs in. This leaves you with a 90 minute window to optimise your recovery. 2-3 hours later have a normal meal with some more protein, this drip feeds the muscles with amino acids resulting in:

stronger muscles = higher intensities = higher calorie burn = leaner muscle mass and the ability to burn more fat at rest.

Hydration

Hydration is so important for female athletes in the late luteal phase. As explained progesterone causes decreases in the blood plasma and increases core temperature, pre hydration can help to minimise the effects.

Energy gels are not sufficient to hydrate you. They are often thicker than the blood plasma and to be absorbed the body needs to be diluted first to facilitate osmosis. The body pulls water from the body to dilute thicker energy gels resulting in dehydration and GI upset.

Water absorption is dependent on sodium and plain water is missing that driver. Plain water can also cause a volume response (you pee a lot). Sodium pairs well with glucose for optimal results.

Similar to the viscous energy gel, too much sodium results in water being pulled back into the GI tract to dilute it.

Aim to consume 3mls per kg of bodyweight per hour (3). 60kg athlete needs roughly 180mls per hour. In warmer climates 4.5mls per kg of body weight per hour is recommended.

References

Nkechinyere, C., Baar, K.. 2018. Effect of Estrogen on Musculoskeletal Performance and Injury Risk. Frontiers in Physiology, 9: pp.1834.

Sheu, W., 2011. Alteration of insulin sensitivity by sex hormones during the menstrual cycle. Journal of Diabetes Investigation, 2(4), pp.258-259.

Sims, S.T. (2016). Roar : how to match your food and fitness to your female physiology for optimum performance, great health, and a strong, lean body for life. New York, Ny: Rodale.

Tehrani, H., et al. 2014.The effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on menstrual cycle, body mass index and hyperandrogenism state of women with poly cystic ovarian syndrome. Journal of Research in Medical Science, 19(9): pp.875–880.

Wojtys, E. M., et al. 2000. Association Between the Menstrual Cycle and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Female Athletes. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 28(5): pp.747.

*Additional resource used was Fitr